Early in the War, the Confederate government built an arsenal in Danville, Virginia. Danville was the terminus of the Richmond and Danville Railroad at the beginning of the Civil War. Transportation of soldiers and supplies on this railroad were vital to the support of Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

The Confederate Arsenal was a few hundred yards east of the Depot. The 140-mile Richmond and Danville Railroad was completed in 1856. The Piedmont Railroad extended a narro guage line 48 miles to Greensboro, N.C. It was not until May of 1864 that that section was completed.

The Confederate Arsenal was a few hundred yards east of the Depot. The 140-mile Richmond and Danville Railroad was completed in 1856. The Piedmont Railroad extended a narro guage line 48 miles to Greensboro, N.C. It was not until May of 1864 that that section was completed.

Until recently, there was doubt as to the exact location of the arsenal. Anne Evans, a Danville native now living in California, found records of eyewitness accounts of the explosion and its location at the end of Craghead Street. Also, the exact date of the accident is still not clear. If you have specific contemporary accounts which give the date send email to dan@rdricketts.com. Dates reported for the incident range from April 11 to April 17, 1865.

One account states that "Pres. Jefferson Davis "left a few hours before the explosion." Since Davis and his cabinet left Danville late on April 10th, that would support the date as April 11, 1865.

Although many facts lean towards an earlier date, some believe that Danville undertaker Jacob Davis was correct in dating the accident on April 17, 1865. On his list, he notes that Mrs. Harrington's son was wounded. George M. Harrington, age 13, died on April 29, 1865 from his injuries in the explosion. Here is the Jacob Davis account:

During this difficult time, it is understandable that mistakes were made in the names and ages of victims. James O. Voss was born on March 8, 1835 and was actually 30 years old. Corp. James O. Voss, son of Paschal and Mahalia Swan Voss, enlisted on April 22, 1861 in THE DANVILLE, EIGHT STAR NEW MARKET and DIXIE ARTILLERY. Although he was paroled at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, he is shown as “killed in action, being blown up on April 16, 1865” in the Pittsylvania County death records. More on Voss below.

Anne notes that George M. Harrington did not die until April 29, 1865, but he is apparently included in the eleven persons that Jacob Davis listed as being buried April 17, 1865. Did the undertaker record this list at a later date and make errors? Did he mean to write April 11, 1865? Were others killed in the explosion not listed in this entry? Can we find reliable resources with the date and more details recorded?

Many soldiers wrote about the accident, but there were few dates. Isaac Gordon Bradwell and other soldiers were waiting for a train in Danville, Virginia after the War had ended. They filled a wash pot with water, some peas and a shoulder of salty ham. As the meal was cooking they wandered over to the nearby Confederate arsenal where they joined others in gathering gun powder and shot. Not long after they returned to the pot, they felt the ground shake and a loud noise.

“We were startled by a tremendous explosion that shook the entire town,” recalled Bradwell, “and pieces of the shell began to drop about us and everywhere in the city. Soon we saw men running with stretchers toward the scene, bringing mangled boys and soldiers away.” Somehow a spark had ignited gunpowder in the arsenal, blowing to bits not only the building, but the crowd of people inside. How many of our brave soldiers perished in this unfortunate catastrophe,” Bradwell said, “ no one will ever know.” (Isaac Gordon Bradwell, Confederate Veteran 1921)

Confederate soldier John Dooley wrote about the night of April 10, 1865:

"As we approached Danville the roads became thronged with stragglers of all descriptions, wagon loads of people and their effects, moving into Danville, and crowds moving away from the town. No one appears to have any settled conviction of what they are going to do or what the government is going to do. All is confusion and panic." Crowds from the surrounding countryside, including stragglers from the Appomattox campaign, gathered around warehouses. These people were more concerned about the necessities of life than the southern cause. A leader emerged from the throng, a " tall woman," who cried out, "Our children and we'uns are starving; the Confederacy is gone up; let us help ourselves." Rioters overwhelmed the passive guards and the "plundering began." The streets cleared, however, when the Confederate ordnance stored near the warehouses was accidentally ignited. Several victims of the explosion lay mangled, and "fragments of [human] limbs were scattered in all directions." The mob thought Yankee soldiers were attacking and scattered to the winds." (From A Long Shadow: Jefferson Davis and the Final Days of the Confederacy, Michael B. Ballard - 1997 - Brown Thrasher Books - The University of Georgia Press)

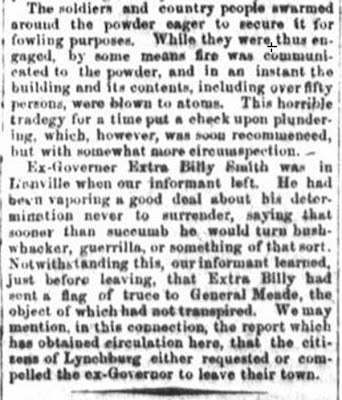

News of the great explosion reached the Daily National Republican newspaper in Washington D.C. at least ten days after the explosion. Here on April 27, 1865, the Richmond Whig is quoted, but the date of the article is not given. The number of dead seems to have been overestimated.

Anne Evans states that this is the only contemporary newspaper account found so far, but she is hopeful other accounts might be found. Perhaps personal accounts may have been recorded by eyewitnesses of the events; either from family members living in the area or soldiers traveling through the area. Can stories be found in William T. Sutherlin's or William C. Grasty's papers, or letters, etc., from others in the region during that time? Accounts closer to the actual event may be considered more accurate and have more details.

Please share resources if you have details about this event. Sart Grasty's account given below, was recorded many years later, in The Danville Bee newspaper in 1929 and may not be totally reliable. But his story offers a unique personal insight into this event. We have also been researching the families of the known victims and hope to share more information in the future.

Edward Pollock's 1885, Illustrated Sketch Book of DanviIle, Virginia; Its Manufactures and Commerce details the events for April 11, 1865 and concludes with... "But so accustomed had the people become to the scenes of suffering and death, that this event, which under ordinary circumstances, would have been justly regarded as an appalling calamity, caused only a passing ripple of excitement, and was soon forgotten except by the relatives and personal friends of the victims." It also noted no one survived that had been near enough to the scene to give to have any exact information.

April 1865 calendar for the month.

Some accounts have the explosion on April 11, 1865 and others April 17th.

This 1877 map of Danville shows the old ferry across Dan River at the end of Craghead. The large one-story building was said to have been a few hundred yards down Craghead Street from the depot near the "sunken road, now filled in," which was the old road to Col. Nathaniel Wilson's Lower Ferry. The grade drops sharply on the east towards the Dan River at this point. The arsenal was on level ground on the west side of the ferry road and on the north side of Craghead. The building was described as having a "high pent roof" (a single sloping shed-type roof).

This 1877 map of Danville shows the old ferry across Dan River at the end of Craghead. The large one-story building was said to have been a few hundred yards down Craghead Street from the depot near the "sunken road, now filled in," which was the old road to Col. Nathaniel Wilson's Lower Ferry. The grade drops sharply on the east towards the Dan River at this point. The arsenal was on level ground on the west side of the ferry road and on the north side of Craghead. The building was described as having a "high pent roof" (a single sloping shed-type roof).Anne recently discovered fascinating descriptions of the tragedy which about 14 people were killed. Sartial "Sart" T. Grasty was a slave at the time belonging to Col.William C. Grasty. Sart and four or five other slaves were brought to Danville from Mount Airy in 1856, when William Grasty bought a fine brick house on Wilson Street. William's son Philip Lightfoot Grasty and Sart were near the same age.

Sart Grasty was an eyewitness to the arsenal explosion. He and his master's son Philip were at the site twenty minutes before the blast and returned twenty minutes after.

The Grasty house on Wilson Street was built by James L. Denny in 1833 (not 1810). Col. Nathaniel Wilson owned a large tract which was outside of Danville at that time. He developed the area as "New Town" in the 1830s when he sold lots. Jefferson Davis and his cabinet evacuated Richmond and traveled on the Richmond & Danville Railroad to Danville and set up a new capital city. The train arrived at 3 pm on April 3, 1865. Cabinet members and Confederate officials stayed with Danville families. President Jefferson Davis stayed with Maj. William T. Sutherlin on Main Street. The government set up executive offices in the old Ann Benedict School on Wilson Street (P. J. Glass is now at that site). The home of William Clark was across the street. On the same lot there were quarters for the Grasty slaves where Sartial T. Grasty lived.

The Grasty house on Wilson Street was built by James L. Denny in 1833 (not 1810). Col. Nathaniel Wilson owned a large tract which was outside of Danville at that time. He developed the area as "New Town" in the 1830s when he sold lots. Jefferson Davis and his cabinet evacuated Richmond and traveled on the Richmond & Danville Railroad to Danville and set up a new capital city. The train arrived at 3 pm on April 3, 1865. Cabinet members and Confederate officials stayed with Danville families. President Jefferson Davis stayed with Maj. William T. Sutherlin on Main Street. The government set up executive offices in the old Ann Benedict School on Wilson Street (P. J. Glass is now at that site). The home of William Clark was across the street. On the same lot there were quarters for the Grasty slaves where Sartial T. Grasty lived.  William C. Grasty owned three lots numbered 145, 147 & 149. The kitchen and slave quarters are shown on this 1877 map. The school on lot 157 is the Danville Female Academy headed by Rev. Geo. W. Dame, the Episcopal Bishop. He ministered daily to the federal prisoners during the Civil War.

William C. Grasty owned three lots numbered 145, 147 & 149. The kitchen and slave quarters are shown on this 1877 map. The school on lot 157 is the Danville Female Academy headed by Rev. Geo. W. Dame, the Episcopal Bishop. He ministered daily to the federal prisoners during the Civil War.

Notice those two outbuildings on the Grasty lot. Slaves were taxed as personal property before the War. On August 1, 1860, Drury Blair recorded the age, sex and color of William C. Grasty’s 46 slaves. He notated that there were two “slave houses.” The oldest was a 65-year-old Mulatto woman. There were 22 males and 24 females many of whom were children and babies. There were six two-year-olds and three under one year old. It is hard to imagine all those people in these two small buildings.

Beginning in 1853, slave births were reported to the courts. William C. Grasty reported three slaves born in the Mount Airy area where his father operated a store. The mothers were not named for Henry, born in July 1853; Adaline, born in November 1853, and Lavena, born in April 1856. After William and family moved to Danville (bringing Sart of several other slaves), a slave named Ann gave birth to twins on August 16, 1858. The boy and girl were named Romeo and Julett. Sartial Grasty said that Wm. C. Grasty purchased him when he was young and that his father was Andrew Banks.

Maj. William T. Sutherlin, who lived not so far away, is recorded as owning 40 slaves in 1860. He is shown to have provided 15 houses for his slaves. Since he was a large tobacco grower most of his slaves were probably scattered on different tracts in the county. This is the area traveled daily by Confederate Pres. Jefferson Davis. Maj. Wm. T. Sutherlin was Quarter Master during the War and Davis stayed at his home at upper left on this 1910 map. In the 1860s, Pine Street curved around to Wilson Street and the Grasty and Benedict houses. The Confederate Arsenal was just over a half mile to the southwest on Craghead Street from these two houses.

This is the area traveled daily by Confederate Pres. Jefferson Davis. Maj. Wm. T. Sutherlin was Quarter Master during the War and Davis stayed at his home at upper left on this 1910 map. In the 1860s, Pine Street curved around to Wilson Street and the Grasty and Benedict houses. The Confederate Arsenal was just over a half mile to the southwest on Craghead Street from these two houses.

Sart Grast remembers seeing President Davis every day traveling to the executive offices for meetings. A small guard accompanied him on the short trip from Main Street down Pine Street to the upper end of Wilson Street. Sart often spoke of holding the horse reigns for Jefferson Davis during that week.

At 3:30 pm on Monday, April 10, 1865, after an all-night ride from Appomattox, Capt. W. P. Graves brought the news of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender of the Confederate Army. Pres. Davis and most of the important officials left that night at 11 pm by train into North Carolina.

There was a fiery explosion the next day at the end of Craghead Street, just a few hundred yards below the depot. The Confederate arsenal had exploded. Thirteen-year-old Sart Grasty and fourteen-year-old Philip Grasty were there before and after the tragic event that killed about 14 people.

The word seems to have spread that the arsenal was no longer guarded and the door had been broken. A large crowd was stocking up on powder and clearing out the ordinance. Sart Grasty said that the powder was ankle deep from overturned kegs. He was worried about the commotion around the dangerous materials. He warned his young master, as quoted in a newspaper story: “Marse Phil, Ise getting scared the way people is carrin’ on.” Philip agreed and they took the horse feed bag filled with dynamite caps and started for home. They walked some distance to the old gun factory near the Danville and Western tracks and sat in the shade facing the Dan River to rest.

Suddenly, about noon, they saw large flames shoot up with heavy black smoke and a deafening roar. They ran back to a large crater that was the arsenal. They saw that there was a great loss of life. The human remains were gathered and buried the next day in one coffin in the cemetery on Holbrook Street (Grove Street Cemetery). Sart was at the funeral and could point to the mound where they were buried. He said that two colored women were blown into the river by the explosion. Other accounts say they ran into the river to extinguish their burning clothing. (based on an article "Confederate Arsenal in Danville Was Blown Up 64 Years Ago Today" - The Bee, Danville, Virginia April 11, 1929 page 9).

Undertaker Jacob Davis recorded in his notebook that the magazine of Danville blew up on Easter Monday, April 17, 1865. But many folks believe that the explosion happened on April 11 instead.

Evidence that the Davis notes are contemporary is that he lists the son of Mrs. M. A. Harrington as wounded.

*Thirteen-year-old George M. Harrington died later on April 29, 1865 from the wounds he received at the explosion. It was said that “he died praying, but in excruciating pain.” His death notice was published in the Sixth Corps newspaper during the federal occupation of Danville.

Among the known dead was Pvt. G. C. Gregg of the 13th Georgia.

*John Smith Vaughn , a private in Capt. J. P. Wykes Co. E. of the Danville Artillery, who lived in the Bachelors Hall community, was killed and left a widow, the former Mariah Jane Dowdy, and five children. His widow, Mariah Jane Dowdy Vaughan, in her 1902 widows pension form, states her husband died in an explosion of a magazine in Danville on April 17, 1865. His family is buried in the Soyars-Vaughan-Lipford Cemetery in the Bachelor’s Hall community. J. S. Vaughn's gravesite is unknown.

Others who died that day were:

* John N. Shepherd, age 12, was a son of W. Shepherd who lived on Wilson Street.

* David Logan, Age 15, son of William Logan.

* A son of James Denny (unnamed).

* "Dooley, William S. B., son of William and Lettie M. Dooley, born Feb. 21, 1853; died April 18, 1865, (A victim of the accidental blowing up of the Confederate States' Arsenal on April 11, 1865.)" ("History of the Old Grove Street Cemetery")

* A slave named Roger, age 13, belonging to Dr. T. P. Atkinson.

* A 14-year-old unnamed slave belonging to William Shields.

* An unnamed slave belonging to James Denny.

(A slave named Bob Ross belonging to Maj. Wm. T. Sutherlin was wounded).

*James O. Voss was a private in Capt. Price’s Danville Artillery (Virginia Light Artillery). The Danville Artillery unit was charged with guarding the arsenal during the War. He is buried in the Voss/Coleman Family Cemetery (Stokesland Cemetery) with his date of death on the headstone as April 15, 1865.

The James O. Voss marker in the Voss/Coleman Family Cemetery (Stokesland). James' uncle, Col. James C. Voss, brother of Pascall, was Commander of the Home Guard in Danville. The house and "Merchant Tailor Shop" of Col. James C. Voss is shown on this 1877 map of Danville. This is the 600 block of Main St. opposite the present Danville House and American National Bank.

The house and "Merchant Tailor Shop" of Col. James C. Voss is shown on this 1877 map of Danville. This is the 600 block of Main St. opposite the present Danville House and American National Bank.

*Tom and Jim were two more victims:

Colonel J. H. Averill, trainmaster in Danville when the arsenal exploded, wrote in 1897: “Two colored boys, twins, about fourteen years old, both bright youngsters, and liked by all. We found Tom fatally injured. We raised him tenderly to take him to the hospital near by. He said: "Jim is there. We found his remains, but he was spared the agony Tom had to endure before death relieved him. The explosion was caused by a soldier dropping a match, and fifty lives were sacrificed through that carelessness."

Back on Wilson Street, William C. and Lettia Grasty were very worried after the explosion because both Philip and Sart were missing. They were relieved when they showed up carried the big bag of explosives and a cavalry sword from the arsenal. Philip’s dad immediately took the bag of dynamite caps and had one of the slaves did a big hole in the back yard and buried the explosives. The cavalry saber was kept in the attic of the old Grasty house for many years. Before Philip’s older sister Jenny, who never married and lived in the home place, gave Sart the old sword and other “trinkets.”

In 1894, Sart Grasty was living at 333 Holbrook Street. In 1931, his address was 327 Holbrook Street. He was there in 1937. Both of these old house have been torn down.

Sartial Grasty was a long-time janitor at city hall. He was apparently well liked and highly respected. He hawked newspapers after work and was often quoted. “Scoop’s Colyum – Wireless Grapevine” received frequent words of wisdom from Sart from 1923 to 1925:

October , 1923: “Winter arrived ‘officially’ at the courthouse this morning. Sart Grasty proclaiming the fact by starting the heating plant of the building going for the first time.”

“Sart Grasty says the nearest approach to perpetual motion is a man hunting a drink.”

“Sart Grasty says he heard a frog croak early this morning and that is a sure sign of spring – but he has not taken off his wool sox yet!”

“The new city hall is the chief topic of conversation on the street, and just as soon as it is decided how big to build it and the architect develops his plan, the digging will commence. Sart Grasty will have to be consulted if he is going to fire the boiler and wind the clock.”

“Sound advice from Sart Grasty: If you would have others think well of you, do something to command their respect – earn, save and provide for future years.”

Sartial Grasty’s wife, the former Eliza Watkins, died on January 10, 1929 and he died on March 17, 1938 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He was living with his sister when he died.

The Freedmen's Cemetery in Danville was originally a part of Green Hill Cemetery. Some slaves are thought to have been buried here during the 1860s. The Freedmen's Cemetery was established for free Blacks and ex-slaves in 1872. The city acquired the cemetery in 1892. There once were about 100 markers, but only about 30 can be found today. Most of those are unreadable.

The Freedmen's Cemetery in Danville was originally a part of Green Hill Cemetery. Some slaves are thought to have been buried here during the 1860s. The Freedmen's Cemetery was established for free Blacks and ex-slaves in 1872. The city acquired the cemetery in 1892. There once were about 100 markers, but only about 30 can be found today. Most of those are unreadable. Watkins plot in the Freedmen's Cemetery. Sartial's wife was Eliza Watkins (1861-1929). These nearby burials are probably her family.

Watkins plot in the Freedmen's Cemetery. Sartial's wife was Eliza Watkins (1861-1929). These nearby burials are probably her family. This 1900 census taken on June 6, 1900 lists Sartial and Eliza's five children. They lived on Holbrook Street. Leonard died on October 1st of that year.

This 1900 census taken on June 6, 1900 lists Sartial and Eliza's five children. They lived on Holbrook Street. Leonard died on October 1st of that year. The census record taken April 22, 1910 lists four children

The census record taken April 22, 1910 lists four children This is the Sartial Grasty square in the Freedmen's Cemetery. The rock wall in the background encloses the National Cemetery where more than 1,300 federal soldiers were buried during the Civil War.

This is the Sartial Grasty square in the Freedmen's Cemetery. The rock wall in the background encloses the National Cemetery where more than 1,300 federal soldiers were buried during the Civil War. Sartial Grasty's head stone in the Freedmen's Cemetery

Sartial Grasty's head stone in the Freedmen's Cemetery

Apparently this is a child who died young

Apparently this is a child who died young Agnes Wiggins was two years youger than Sart and may have been a sister

Agnes Wiggins was two years youger than Sart and may have been a sister This is the High Street Baptist church in Danville where Eliza's funeral was held in 1929.

This is the High Street Baptist church in Danville where Eliza's funeral was held in 1929.

The house at left is 327 Holbrook Street. Sart Grasty lived here until shortly before he died in 1938. The older houses have been torn down. In the distance on the corner or Holbrook and Gay Streets is the large Loyal Baptist Church building. Sart Grasty attended High Street Baptist Church which is a few blocks east and to the right of these houses. I have had this old 1835 letter for a long time. Competition is the old name for Chatham the Pittsylvania County Seat. I am not sure who this Grasty is. The writer, William Johns Hamlett is talks about a girl who is the "Belle of Danville."

I have had this old 1835 letter for a long time. Competition is the old name for Chatham the Pittsylvania County Seat. I am not sure who this Grasty is. The writer, William Johns Hamlett is talks about a girl who is the "Belle of Danville." About another Danville girl "Miss E.__ M.___", Hamlett writes "Oh! Grasty, Love, it is a painful thing." I believe that this is the William J. Hamlett who was a long-time postmaster in Anderson County, Texas who died on December 9, 1891.

About another Danville girl "Miss E.__ M.___", Hamlett writes "Oh! Grasty, Love, it is a painful thing." I believe that this is the William J. Hamlett who was a long-time postmaster in Anderson County, Texas who died on December 9, 1891.

The most detailed account that we have found is by Robert Enoch Withers, M. D., written in his book, Autobiography of an Octogenarian (1907). He served as Colonel of the 18th Regiment of Virginia Infantry during the War. Dr. Withers does not give an exact date but starts the story "around the thirteenth of April.”

Dr. Withers graduated from the University of Virginia in 1841 and practiced medicine in Lynchburg until 1858, when he came to Danville, Virginia. He was a Union supporter until troops were raised to subjugate southern states. He volunteered in the Confederate Army in April 1861. He was commander of the 18th regiment of Virginia infantry until he was badly wounded. Col. Withers was leading a charge at the Battle of Gaines Mill on June 27, 1862. When he reached within 40 yards of the Union lines, a minie’ ball tore into his lung. His mouth and throat filled with blood as he fell from his horse. As two soldiers were carrying him to the rear, another bullet struck Withers in his back. He was hospitalized until February 10, 1863 and then placed on the retirement list. Soon after, he accepted the assignment to command the prison post of Danville.

This is Col. Withers account of the events of April 1865 from his 1907 book:

“About the thirteenth of April the town was filled with soldiers returning South after the surrender at Appomattox, the greater number of whom were in an utterly disorganized condition, with no officers in charge; and worse than this, crowds came in from the surrounding country, attracted by the reports that large quantities of Government supplies were stored in Danville which could be had for the taking, and they thronged the streets bent on plunder. The disbanded soldiers were crazy for clothing and food, and the mob of country people would point out Government store houses and tell the soldiers that they were filled with shoes and clothing or flour and meat. Crash! would go the doors at once, and the soldiers would rush in to find nothing that they cared for, but the mob would follow them and speedily carry off everything they could lay their hands on. The situation was rapidly becoming critical, so much so that a called meeting of the Council was held and the danger confronting the community was anxiously considered. The police were confessedly unable to cope with the rioters, and it was finally proposed to send a committee to me, with the request that I would take charge of matters and do what I thought best -to protect the lives and property of the citizens. This proposition at first met with favor, but before final action was taken, someone suggested that if it were done, "Colonel Withers would certainly put the town under martial law and force all the men in town to do guard duty." They finally adjourned without doing anything, except to order an additional number of policemen to be sworn in.

The next day matters were decidedly worse. In the early morning I was informed that a mob headed by a returned soldier who lived in Danville, of gigantic size and great audacity, was visiting the dwellings of prominent citizens, demanding that they should be allowed to search the house, for the purpose of getting possession of the large supplies of sugar, flour, and bacon believed to be stored therein. I called out the guard and rushed with them to the house where the mob was reported to be, found they had just left to visit another dwelling in the upper part of the town. I pushed on to this place, and met the Mayor at the head of his augmented force of policemen, who had succeeded in dispersing the mob and arresting their leader.

The Mayor was James Walker, a plucky fellow, who had fired at the leader of the mob, barely missing him, and showing that he meant business, when they immediately scattered. About ten o'clock I was summoned to the railroad station, where about two thousand returning soldiers were said to be looting all the houses in the vicinity. I reached the spot as quickly as possible, and found the country people occupying the Arsenal and Armory, and carrying off everything they could lay their hands on, the buildings having been first broken open by the soldiers in the belief that they were stored with food and clothing. The soldiers said all they wanted was transportation home, but the railroad Superintendent would not start any train. I went to his office and found him pretty drunk but with sense enough to know what he was about. I asked why he did not send off a train with these soldiers, he said he had done his best but the railroad men were so demoralized that they would do nothing to aid him. He could get no one to pump the water to fill the tank of the engine, and wound up by saying they might all "Go to h-11, both soldiers and railroad as for him."

Going back to the station, I jumped on a flat and calling to the soldiers commanded "Attention!" in a loud voice, and secured it. I then explained the cause of the delay, and called for volunteers to pump water for the engine. Some men came forward and said they were willing to do this, and in fact had made the effort, but as soon as they commenced to pump the train was filled with others until no place could be found for those who had pumped the water. I told them I would put guards at the doors of every coach and would permit no one to enter until the men who had pumped the water were accommodated. By the assistance of several officers who were in the crowd, this plan was carried out and the train started.

I then made an effort to get another train off in the same way and while standing at the tank, I was startled by a tremendous explosion near me. The Arsenal stored with cartridges, loaded shells, and similar munitions went up in smoke, but for some time there was heard the sound of exploding cartridges and occasionally of a shell, simulating precisely the sound produced by a pretty brisk skirmish in which both artillery and small arms figured. As I afterwords ascertained, the impression up town was that the Yankee army had arrived and was firing on the town. The effect of this was seen in the speedy rush of all the country people from the town, which was evacuated in about five minutes.

The cause of the explosion was never definitely ascertained, as all the persons in the building were killed, I believe, but it can be easily understood that a lot of boys and young men engaged in breaking open cartridges and collecting the powder, would soon fill the floor with waste powder, which might ignite from the spark of a pipe or cigar with such consequences as ensued that day.

There were, however, some comic features mingled with the tragic scene, and I think I never witnessed a more ludicrous spectacle that that presented by an old crone from the "Mountain Hills" who ran past me on her way to the railroad bridge with her petticoats way up above her knees and carrying three guns in her hands which she had secured at the Armory. She made no pause but ran for life, clutching her plunder in tenacious grasp.

Just before the explosion, the Mayor sent me a message to come up town quickly, as the mob were in complete possession and the police could do nothing with them. Telling the messenger to return at once and tell him I would be there in a few minutes as I only awaited the starting of the train with the soldiers, but to get all his force of policemen in a body ready for action by the time I reached him. I started up town in five minutes after the explosion, but when I reached there I could see no semblance of a mob on the streets. They had vanished utterly.

The town people were by this time almost in a state of panic. The Council met at night and at once agreed to ask me to take charge of matters and do what I could to protect the lives and property of the people. I at once accepted the trust, and went to work to organize the citizens between sixteen and fifty years in squads of twenty, armed them and sent a guard to each bridge, ferry, and ford that gave access to the town, and to place pickets on every road leading into it, with orders to permit no one from the country to enter town without a pass from me.”

In conclusion: Anne and I concur with Chris Calkins and most of the authors mention above, that the event likely happened near time of the surrender and the exit of President Davis from Danville. Would folks have waited until April 17,1865 to raid the arsenal? Most all sources reviewed, record the event before the death of President Lincoln on April 15, 1865. So even if some writers did not mention the April 11 date precisely, most gave the sequences of event happening before Lincoln died.

We gladly seek input from others with different opinions, but please "show us your evidence!"

"We are, like the survivors, fast passing away, and will soon be known no more." (Col. J. H. AVERILL in 1897).

Special thanks to the writers and librarians that responded to our requests for information. And thanks to our readers for sharing their ideas and their love of history.

(see related blog: http://stokeslandcemetery.blogspot.com/ )

Article, photographs and maps copyright 2010 by Robert D. Ricketts.